The $20,000 Temptation

When I tell my students we are going to be watching a movie in class, they get excited. They then ask me what it is, and when I tell them It’s a Wonderful Life, most of them lose a bit of that fervor. When I tell them that it’s black and white and from 1946, the entire temperature of the room changes.

I am sure I am not alone in this. Our students cannot wrap their heads around the fact that a movie, in its desaturated form, can still be a good movie. If it doesn’t have incredible special effects and gratuitous mature content, many of them have zero interest.

But then I start talking through this film and why it isn’t just one of my favorite Christmas movies, but one of my overall favorite movies, and some of them start to lean in.

This film isn’t just a cozy holiday classic. It’s a case study in character, consequence, and what it actually looks like to do the right thing when it costs you something. That’s why I keep coming back to it—not just as a film teacher, but as a teacher of human beings.

And that’s why I think we should be unapologetic about showing films in our classrooms—not only to teach craft, but to teach morals.

Not ideology.

Not politics.

Morals. The basics of right and wrong, integrity and compromise, selflessness and selfishness.

The $20,000 Temptation

One of the richest scenes in It’s a Wonderful Life is the meeting between George Bailey and Mr. Potter.

Potter, the ruthless businessman who’s spent the entire movie trying to crush the Bailey Building & Loan, suddenly changes tactics. Instead of fighting George, he tries to buy him.

He offers George a job with a salary of $20,000 a year.

For context: back then, that would have been close to ten times George’s current salary—easily the equivalent of well over a quarter of a million dollars a year today. In other words, this isn’t a modest raise. It’s life-changing money: a big house, travel, security for his kids, prestige, everything.

And George almost takes it.

You can see it in the way he sits down, the way his tone softens, the way his eyes drift as he imagines what this could mean. For a moment, he’s all of us weighing the deal of a lifetime.

But then something shifts. He realizes what he’s agreeing to and, more importantly, who he’d be tying himself to. He stands up, pulls his hand back from Potter’s, and walks away.

He doesn’t moralize. He doesn’t give a long speech. He just knows: “I don’t want to be in business with this man. No amount of money is worth becoming who I’d have to become to work for him.”

That’s a powerful moment for a film student.

It’s an essential moment for a human being.

Why This Scene Belongs in a Film Classroom

We can (and should) talk about this scene in terms of craft:

Framing: Potter seated, George standing—visually signaling power and temptation.

Performance: the micro-expressions on George’s face as the offer sinks in.

Blocking: the physical distance between them at the end of the scene.

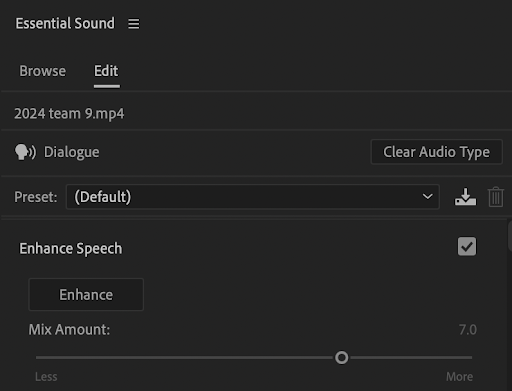

Sound and pacing: the way the silence stretches as George “hears himself” agreeing.

All of that is gold for teaching camera language, performance direction, and scene structure. But if we stop there, we miss the bigger gift.

This scene is a ready-made discussion starter about:

What you’re willing to compromise for success

Who you choose to work for and with

The line between ambition and selling out

How “opportunity” sometimes comes from people who don’t have your best interest at heart

Every one of our students is going to face some version of that moment—maybe not with a cigar-smoking banker in a three-piece suit, but with a job offer, a social group, a creative collaboration, or a shortcut that feels too good to be true.

Film gives us a low-stakes way to rehearse those high-stakes choices.

Films as Moral Case Studies (Without Turning Class Into a Sermon)

Students tune out when they feel like they’re being preached at. But when the story is doing the heavy lifting, they’ll stay engaged a lot longer—and think much more deeply.

Here’s how I approach it with It’s a Wonderful Life and scenes like the Potter offer:

Start with observation, not judgment.

I don’t open with, “So, class, what’s the moral lesson here?” That shuts things down.

Instead, I’ll ask: “What does George want in this moment?” “What do you think is going through his head when Potter mentions the salary?” “At what exact moment do you think George changes his mind—and why?”

We stay in the realm of character and motivation first. Students are usually quick to point out the tension between George’s dreams and his values.

Move to real-world parallels

Once they’ve analyzed the scene as filmmakers, I’ll pivot:

“Have you ever heard the phrase ‘guilt by association’? Or ‘those who lie down with dogs, rise up with fleas’?

“What does it say about a person when they’re willing to work for someone they don’t respect?”

”Can you think of a situation (in media, sports, or real life) where someone took the deal and regretted it later?”

Now we’re still talking about the film, but it’s connecting directly to their world.

Keep ideology out of it; keep morality in it

This is about honesty, loyalty, courage, greed, integrity—not about political labels or culture-war nonsense.

I’m not telling students what to think about everything.

I’m helping them practice how to think about something: temptation, compromise, and character.

That’s not indoctrination. That’s education.

Why This Matters Specifically for Film and Video Students

Our students aren’t just consumers of media; they’re future creators, crew members, editors, directors, and influencers.

That means:

They’ll have opportunities to shape narratives.

They’ll be asked to promote brands, people, and ideas.

They’ll be tempted—sometimes strongly—to say “yes” to projects or employers that conflict with their own values.

If all we teach them is how to “get the shot” and “hit the deadline,” we’re only doing half the job.

Scenes like George and Potter give us a chance to ask:

“Would you work on a project for someone like Potter?”

“Would you take a huge paycheck to promote something you don’t believe in?”

“What line would you personally refuse to cross, even if everyone else said it was normal?”

Those aren’t hypothetical questions for kids headed into media. That’s their likely future.

Practical Ways to Use This Scene in Your Classroom

If you want to build this into your own lesson, here are some simple approaches:

Shot-by-shot breakdown + moral reflection

Have students:

Watch the scene once with no interruptions.

Watch again, pausing to analyze framing, performance, and dialogue.

Then answer writing prompts such as:

“What does this scene reveal about George’s character?”

“What is Potter really buying if George says yes?”

“Write about a time you almost said yes to something you knew was wrong.”

You’ve now done both film analysis (formative) and character reflection (also formative).

Rewrite the scene

Ask students to write a short alternative version where:

George does take the deal. How does he justify it?

Or Potter offers even more control and power instead of money. What changes?

Then follow it with a discussion:

“Did you feel good about your version? Why or why not?”

“What long-term consequences do you think your George would face?”

This ties directly into screenwriting skills while staying routed in moral decision-making.

Connect to career readiness

Have students imagine a real-world scenario:

“You’re a freelance editor or content creator. A client with a sketchy reputation offers you a huge sum for a series of videos that you know will mislead viewers. What do you do?”

Then have them:

Write a professional response email declining the work, or

Write a code of ethics for themselves as media creators.

Now the lesson lines up beautifully with CTAE & AVTF goals around professionalism, employability skills, and ethical practice.

The People We Choose To Stand Beside

The thing that hits me hardest in that office scene isn’t the money. It’s the moment George realizes who he would have to become to sit comfortably across from Potter every day.

In that instant, the real question isn’t: “How much is this job worth?” It’s: “Who do I become by taking it—and who am I standing with?”

That is a conversation worth having with teenagers.

Films like It’s a Wonderful Life give us the perfect framework: emotionally engaging, narratively rich, technically well-crafted, and morally grounded without being preachy.

So yes, keep teaching shot composition, continuity editing, lighting, and story structure.

But don’t underestimate the power of a scene like George vs. Potter to do double duty:

Teach students how to make better films.

Teach students how to live better lives.

If we can accomplish both in the same 90-minute block, that’s not “just showing a movie.” That’s good teaching.

Meet the Author, Author Name

Author Bio

As summer winds down, the familiar rhythm of a new school year approaches. For educators like James Peach, the weeks leading up to students' return aren't just about shuffling papers; they're a strategic dance of preparation, aiming to ignite inspiration and cultivate self-sufficiency.